Hot IPOs are becoming rarer in the late stages of this post-GFC bull market cycle.

The primary reason for that is that private market financing allows early-stage firms to remain private longer.

This trend is turning around, starting with the IPO of cloud data platform Snowflake (SNOW) in September, with several other hot upcoming IPOs like Asana, Palantir, and Unity Software.

As such, we’re likely to see a slew of hot tech IPOs, should the market rally continue.

Why IPOs Are Different

One of the significant fallacies of typical trading books is assuming that all markets trade similarly; that you could apply the same strategy to any market.

One of the ordinary circumstances is to present a technical trading pattern and claim that it’s tradeable on any timeframe, any market.

This conventional wisdom is flawed at best.

Each market presents different incentives, transaction costs, margin requirements, and participants that dictate the market action. Here’s why IPOs are different.

Few Significant Levels

An IPO which has just begun to trade has no critical support and resistance levels, or recent extreme highs or lows.

As such, there are no predictable zones of increased trading activity.

There’s no areas where stops are likely clustered, no support zones where hedge funds are accumulating positions, and no resistance zones where bagholders will sell to break-even (at least nothing that you can ascertain through chart analysis).

Incentives

One of the big talking points floating around about IPOs right now is the perceived unfairness of share allocations.

Many prominent people in the finance world are talking about this right now, including prominent venture capitalist Bill Gurley. Among many other things, Gurley says that IPO underwriters structurally underprice shares to please clients with allocations.

An academic paper recently came out in August 2020, called Nepotism in IPOs: Consequences for Issuers and Investors from the Swiss Finance Institute, which backs some of Gurley’s claims, namely that they “find a strong positive association between IPO underpricing and affiliated allocations.”

Low Floats

In an IPO, company insiders and private investors are selling their shares to the public. In the vast majority of IPOs, only a small portion of shares outstanding is part of the free float, which can be freely transacted on an exchange.

The rest of the shares remain held by company insiders, wrapped up in restricted employee stock, etc.

Andreessen Horowitz says that the typical IPO only has 1 to 3 percent outstanding shares in the free float. So you have a situation where the vast majority of shares outstanding aren’t in the tradeable free float.

In hot IPOs, allocations are hard to come by, forcing excited investors to trade the stock on day one of trading. This skews the demand sharply, which partly explains the outstanding first-day performance of IPOs.

Are IPOs Structurally Underpriced?

Going back to Andreessen Horowitz, one of the most well-respected VC firms in the world argues that the flaw of IPOs isn’t so much a factor of structural underpricing, but the low float, as discussed in the previous section of this article.

They explain how IPOs are priced similarly to how a NYSE Specialist used to choose the opening price for a stock on a given day. Upon examining the order book, the “best price” that would facilitate most trade is chosen.

The difference is, that only one price is ever chosen instead of a specialist opening a stock, where the stock can trade at any price following the opening print.

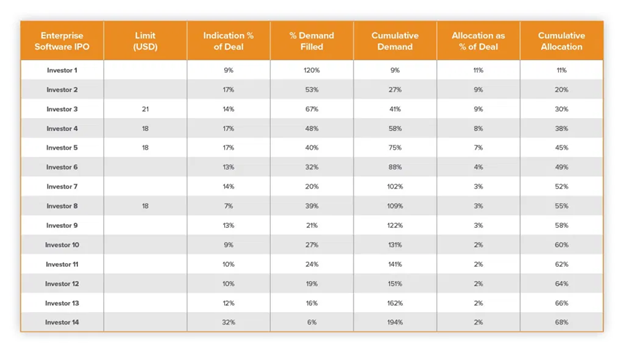

They give an example of a real order book from a recent software IPO to demonstrate their point:

The argument is that underwriters dictate IPO prices based more on aggregate demand, aka where price can “clear” the most orders, instead of the popular narrative that they choose it based on their whims, or what will be favorable for first-day traders.

Their explanation for first-day IPO pops is simple: there’s a limited amount of shares available for trade.

In hot IPOs (where allocations are difficult to attain), interested first-day traders and investors outweigh the float, pushing the price up considerably.

The Data on Trading IPOs

Hot vs. Cold IPO Markets

The structural underpricing and hence, the strong first-day performance of IPOs is a common surface-level IPO statistic that many traders are aware of.

While these numbers aren’t inaccurate, they don’t tell the entire story.

Just like equity markets as a whole, IPOs go through hot and cold periods. Predictability, during hot IPO markets, underpricings are more significant, leading to stronger first-day performance.

Conversely, in cold IPO markets, the risk of overpricing is considerable, which of course, leads to first-day underperformance.

What’s interesting about these two environments is that ‘cold’ IPOs tend to have stronger profitability, while still underperforming ‘hot’ IPOs in aggregate.

Common sense tells us that investors don’t want to buy money-losing, early-stage firms in a bear market, so this makes sense.

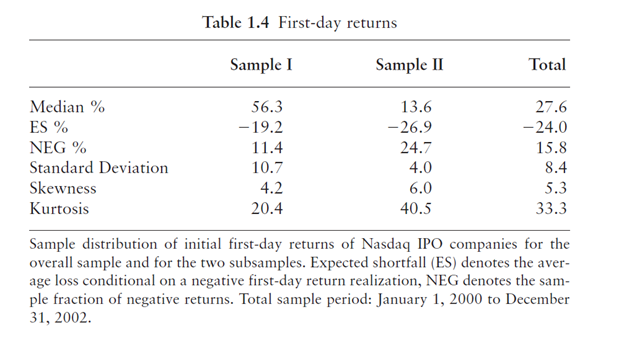

See the graph below, which compares IPOs during the Nasdaq dotcom boom (Sample I) to IPOs during the subsequent bear market (Sample II):

As you can see, not only is the median first-day return for hot IPOs a multiple of cold IPOs, but the risk of a negative return is much lower, as marked by “NEG %.”

All in all, for short-term trading purposes, hot IPO markets offer many attractive opportunities, while cold markets serve fewer with comparatively poor performance.

Niklas Wagner, author of the paper Nasdaq IPOs Around the Market Peak in 2000, is responsible for these findings. His paper was published in Initial Public Offerings: An International Perspective, an excellent compilation of IPO studies.

Structural IPO Underpricing

IPO underpricing is a main focal point of this article.

As seen in evidence from the previous section, IPOs tend to go up on their first day of trading, even in cold markets.

For this, many reasons are stated from adverse incentives for underwriters to the pent-up demand for new issues coupled with low floats.

One of the primary academic works on underpricing is Alexander Ljungqvist’s IPO Underpricing.

In it, he presents four broad theories for underpricing, all with their own merit:

- Information asymmetry: Either the investors, issuing firm or underwriters know more than the other parties

- Behavioral: Traders and investors bidding up the price based on factors unrelated to the firm’s intrinsic value, like the knowledge the IPOs are structurally underpriced

- Control: underwriters and insiders use underpricing to control who owns their stock pre-IPO to avoid problems with unfavorable public shareholders

- Institutional: Structured to avoid or optimize for taxes, potential litigation, and price stabilization

Lundqvist estimates the average underpricing of US IPOs since the 1960s is 19%.

IPO Lockup Market Reactions

The typical IPO will have restrictions on when insiders can sell their shares, referred to as the ‘lockup period.’ In past hot IPOs that performed very well for several months, like Tilray, the lockup period was frequently discussed in financial media.

Because the price deviated so far from its IPO price and, theoretically, it’s intrinsic value, the assumption is that shareholders should sell when their lockup period expires. This will push the price down considerably.

We can see real-life examples of this in stocks like Tilray (TLRY) and Beyond Meat (BYND). Both were post-IPO high flyers and saw significant bearish price activity in the leadup and following the expiration of IPO lockups.

Here’s Beyond Meat (BYND). The red arrow marks the date of the lockup expiration (October 29, 2019).

Roughly 80% of the company’s shares outstanding were added to the float up the lockup expiration.

Here’s Tilray (TLRY). The red arrow marks the lockup expiration.

There’s academic evidence to support this phenomenon too. Market Reactions to the Expiration of IPO Lockup Provisions has some interesting findings, primarily, the significant abnormal negative returns leading up to, on the day of, and following IPO lockup dates.

One friction to shorting these IPO lockups is that these stocks’ short borrow rate tends to surge prior to the lockup date.

You have to believe there’s a huge dip coming to justify paying the hefty interest rate.

Trading IPOs

Trading IPOs on opening day can be very different compared to trading other stocks. There are no support/resistant levels established yet and emotions are high with excitement and expectations.

One of the best ways to handle hot IPOs is to wait for the morning trading craze to cool off and allow the stock to establish some ‘price discovery‘.

This will give you levels to trade off and price action will likely be less erratic and volatile.

Having levels to trade off helps you manage risk, which is your number one goal when trading an IPO. Placing hard stops and managing trade size is a must.

Trading on the side of momentum tends to be a better strategy with IPOs, especially for new traders. Trying to fade tops and pick up bottoms can be difficult during volatile trading.

You can learn more about trading IPOs in our Day Trading Courses.

Bottom Line

The IPO process is complex, and the real juicy details about it are mostly proprietary.

Because I’m not an institutional investor with experience talking to underwriters or even other institutional IPO investors, I can’t speak to whether one view of the process is more accurate than the other.

The academic evidence is pretty clear that there are exploitable tendencies around IPOs.

However, they’re hard to take advantage of, especially for the average retail trader or investor.

First off, getting an allocation to a hot IPO is very difficult, so to realize the edge outlined in the academic evidence, you’d have to buy at the offering price, which is frequently unavailable.

When it comes to short selling the IPO lockup dip, locating shares and outpacing short borrow rates becomes a concern which will, at the very least, significantly eat into your profits.

With all of that said, edges are hard to find. When you do find them, they’re usually hard to act on. That’s markets for you. There’s no free lunch, after all.